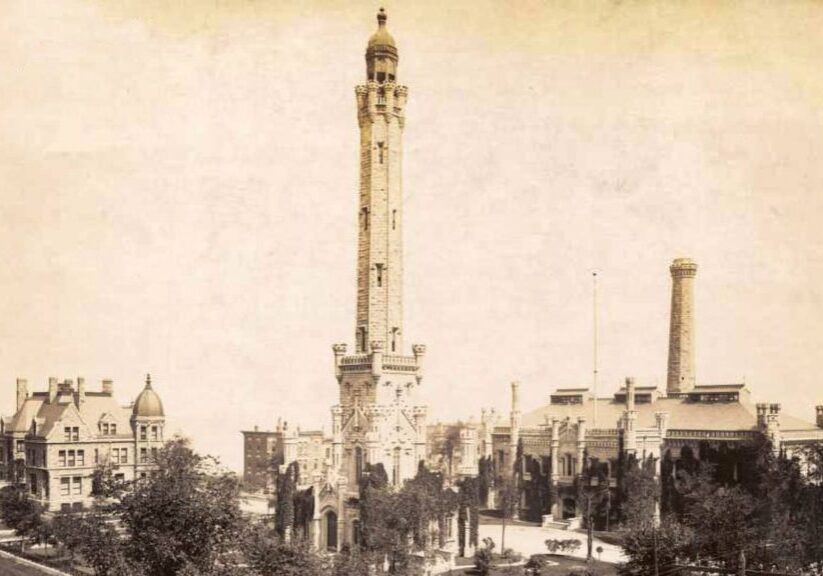

Chicago Water Tower and Chicago Avenue Pumping Station – 806 N. Michigan Ave. “The flames from this time spread with such rapidity that the whole neighborhood for blocks around became a ‘sea of fire’, thus at about 3 o’clock in the morning of the 9th of October the pumping works became an utter wreck, nothing but the naked walls of the building and blackened skeletons of three engines were left to mark the spot from whence only a few hours before flowed millions of gallons of pure water for the comfort and convenience of our citizens”.

– City engineer (and later mayor) DeWitt Clinton Creiger

By Julie Jonlich

A lot has changed in 150 years since that warm, windy autumn night in a small barn behind 137 De Koven St. (now 558 W. De Koven St., and current home of the Chicago Fire Department Quinn Fire Academy) which changed the course of Chicago’s history. Here’s a look at some of the surviving structures from the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

Saint Ignatius College Prep 1076 W. Roosevelt Rd.

Founded in 1869 by Fr. Arnold Damen, S.J., a Dutch Jesuit missionary to the United States, Saint Ignatius College (now Saint Ignatius College Prep) is one of the few public structures that predates the Chicago Fire of 1871. The school, which reopened two weeks after the fire, was home to displaced orphans and Bishop Thomas Foley, whose residence downtown had been destroyed. The Bishop thanked Father Damen for his hospitality by donating money for a Natural History Museum that was expanded in 1887-1888. Now known as the Brunswick Room, its cabinets, galleries, and staircases were built by the famous billiard company founded by Swiss immigrant John Moses Brunswick.

Church of the Holy Family 1080 W. Roosevelt Rd.

Just a mile away from the alleged starting point of the fire, shining brightly in the east transept of the church (Patrick and Catherine O’Leary’s parish at the time of the fire), are the seven lights Father Damen vowed would burn forever, if the church was spared from the fire. Praying throughout the night, while away in Brooklyn, NY preaching a mission at St. Patrick’s Church, Damen invoked Our Lady of Perpetual Help to protect the church and its nearby structures, vowing to light 7 candles in front of her statue.

Old Saint Patrick’s Catholic Church 700 W. Adams

A strong wind from the southwest kept the fire from reaching St. Patrick’s Church, located about a mile northwest of the O’Leary’s barn. Built by Irish immigrants, St. Patrick’s provided charitable services to many who survived the fire. Designed by architects Asher Carter and Augustus Bauer, the current church is made of Joliet limestone and Milwaukee brick. Dedicated on Christmas Day, 1856. Old St. Pat’s Church is the oldest public building in Chicago.

St. Michael’s Catholic Church 1633 N. Cleveland Ave.

As the fire blew north, past downtown, parishioners of St. Michael’s Church in Old Town are said to have packed the church’s treasures into an oxcart and fled. Shortly after, all the parish buildings were destroyed, with only the walls of the church standing. Less than a week later, the church began re-building. Two years later, the re-constructed St. Michael’s Church was consecrated and dedicated, making it one of the first Chicago churches to rise from the ashes.

Richard Bellinger cottage (private residence) 2121 N. Hudson

One of the few north side homes to survive the fire. This home in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood belonged to Chicago police officer Richard Bellinger. To save the house from destruction, he allegedly put wet blankets on the roof, and then turned to his store of cider when the water ran out. Assisted by his brother-in-law, Bellinger also cleared the dry leaves that were on the property, tore up the nearby wooden sidewalk and fence, and snuffed as many sparks as he could as soon as they landed.

Hull House 800 S. Halsted St.

The Charles J. Hull mansion, constructed in 1856 is just a few blocks from where the fire started. Completely spared from the flames because of the wind blowing northeast. This National Historic Landmark did not take on significance until 1889, when Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr began using it as a settlement house.

*Photo provided by the Chicago History Museum